Mollie and the Massacre: A Sad History of the Verbias Family

Trigger Warning: This post contains details of abuse and fatal injuries to a minor

A deadly shadow followed the Verbias family of Niles, Ohio for years, leaving horror, tragedy, and destruction in its path. Today, the family would be termed dysfunctional, the children neglected, abused, and allowed to run wild. The walls of their Belmont Avenue home could not contain their instability, their conflicts leaching outdoors for all the neighborhood to witness. When a daughter was discovered murdered, their darkness became exposed to the public and a son began a lifelong mission to take “a lot of people” with him to the grave.

A Body In the Brush

Thursday, July 21, 1921

Niles, Trumbull County, Ohio

Two little boys entered a grassy area off of Russell Avenue on their way to pick berries when they stumbled across a decomposing body. Some five or six-hundred feet from the road, lying face-up in the tall grass was a teenaged girl wearing a simple blue sundress and lightweight slippers. A dark blue straw hat lay nearby. The body belonged to 14-year-old Molly Verbias who lived nearby with her family.

The Autopsy

Mollie’s body was discovered at 2:35 p.m. and she was presumed to have been dead for at least several hours, the summer heat hastening decomposition. The evidence suggested that Mollie had been killed elsewhere and moved to the location her body had been found. Investigators believed the sundress she wore had been placed on her body after she was killed as it had no drops of blood on its fabric and was not ripped during her death throes. The ground around her body was undisturbed, with no indication a struggle had taken place there.

Holloway’s ambulance removed Mollie’s body from the scene and took her to their Niles morgue where Coroner Henshaw, attended by Doctors Thomas and Elder, conducted an autopsy. Her cause of death could not be immediately discerned, though slight markings were visible on her neck. On Mollie’s side, Henshaw found indents of teeth and believed she had been bitten. Her body showed no signs of having been sexually molested before or after death.

Besides the impressions on her neck, the doctors theorized a rope could have been used to strangle her. They believed the markings on her throat were consistent with fibers wound tightly about her neck, but such a weapon could not be found near the crime scene. Henshaw was not quick to rule strangulation because he believed the impressions on Mollie’s throat were not deep enough to cause death and could be explained by postmortem insect activity.

Though a cause of death was not immediately released, the local papers pushed the notion that Mollie had been choked to death.

Marks upon the child’s throat are of a peculiar type. The fingerprints seem to be made by a hand, small but strong, such as a woman might possess. The windpipe seems to have been clutched by some powerful fingernails, inflicted when the child made a frantic death struggle and the victim’s death hold was tightened.

– The Niles Daily News, July 22, 1921, Page 1

Another theory besides murder, was the possibility that Mollie had ingested poison, either intentionally or accidentally. She could have accidentally ate poisonous berries in the woods without knowing the difference between them and the edible ones. A person who had swallowed poison could claw at their own throat in such a manner to cause comparable markings before succumbing to the toxic effects. Henshaw wanted to rule out such a possibility, so on Friday morning he sent Mollie’s stomach to a local pathologist, R.C. McBride, to study its contents. He then returned the girl’s body to her family’s home so they could prepare for her funeral.

A Troubled Family

Mollie, described as “pretty”, “attractive”, and appearing older than her years, was the daughter of Joseph Verbias and Elizabeth Botciti who lived at 602 Belmont Avenue, an address that no longer exists. She had two older siblings, Helen and Alex, and four little sisters. She attended the 5th grade at Bentley Avenue School.

The Verbias family immigrated from Barkasso, Hungary, departing from Fiume on the ship Franconia and processed through Ellis Island in New York City on December 26th, 1913. They settled in Niles, Ohio, the state that received the highest amount of Hungarian immigrants in all of the United States. Most made their homes around Cleveland and Youngstown where factories reigned the landscape and work could be obtained.

The oldest daughter, Helen, married Steve Laboda in 1917 when she was fifteen years old. Prior to the marriage, she attempted suicide and when asked why she wanted to end her own life, she claimed her mother had treated her so cruelly that she could not bear to live any longer. Her marriage proved a welcome escape from the evil within their Belmont Avenue home, but her younger siblings were left behind to live in the chaos.

The neighbors claimed Mollie lived in a chaotic, abusive household and they often heard her cries as she was beaten frequently and with a brutality unacceptable to inflict on a child. Her screams could even be heard the afternoon prior to her body’s discovery as her mother whipped her fiercely.

One month before Mollie’s death, Mrs. Verbias pressed charges against 34-year-old Gasper Logar of Niles, alleging that he had held Mollie hostage overnight in his locked bedroom. The Hungarian-born Logar was crippled, his right leg having been amputated above the knee. He had left a wife and child in Hungary. Logar was acquitted due to lack of evidence against him. The weekend before her murder, Mollie again ran away and her parents went in search of her. She was missing for three days. On Sunday, a policeman found her wandering in Girard and brought her home. The wrath she suffered as a result was heard by the neighbors.

The Hunt For A Killer

Police Chief Rounds immediately put his officers on the task of searching for clues about the field and Mason’s woods. County Detective Gillen joined the men in the gathering of evidence, particularly searching for any bloodied clothing or indication of the kill site. The search fanned out for a mile in every direction from the location Mollie’s body had been discovered.

A group of civilians took to the woods in search for Mollie’s murderer in hopes he was hiding out beneath the cover of brush and foliage. They carried rifles, shot guns, and clubs. Mollie’s death had arrived at the heels of an attack on a Niles woman, 51-year-old Elizabeth Dellinger and assaults of two New Castle girls. The suspect of the Dellinger assault had been arrested, but that fact did nothing to calm the city’s frayed nerves. The entire community was on edge and prepared to capture the coward who had taken the life of a young girl.

When Chief Rounds questioned Mollie’s mother, he discovered she understood hardly a word of English and could speak very few words outside of her native language. Employing an interpreter, he was able to obtain a statement, though this method made it very difficult to accurately discern Mrs. Verbias’ state of mind. She claimed she had last seen Mollie alive when the pair took their cow to the pasture around five o’clock Wednesday evening. Mollie ran off to pick berries in the bushes and her mother returned home, leaving her daughter behind. She claimed Mollie did not show up at the house that night, but was not alarmed and did not go in search of the girl. This fact puzzled police and when questioned of why she had no concern over her daughter’s disappearance, Mrs. Verbias stated Mollie had been in the habit of running off and not coming home for the night. Mrs. Verbias claimed Mollie had exhibited this “wanderlust” for three years, therefore was unconcerned for her daughter’s welfare.

When asked about the abuse witnessed by the neighbors, Mrs. Verbias declared Mollie to be a rebellious child and professed the beatings were the only method of keeping her daughter in line. According to her, the severe manner of punishment was justifiable. During the cross-examination, Mrs. Verbias fainted twice, and the police called a doctor to tend to the woman. Mrs. Verbias did not shed a single tear during the questioning, but she did moan and call out for Mollie. Finally, due to Mrs. Verbias’ unerring hysterics, the doctor ordered police to end the questioning and allow Mrs. Verbias to return home.

Chief Rounds brought Gasper Logar into the station and interrogated him forcefully. However, due to lack of evidence and the near physical incapability for Logar to have carried her body into the pasture, Logar was released.

At 2 o’clock on Friday the 23rd, investigators had formed no verdict and Chief Rounds released a statement.

We have no information to give out in connection with the case. The death of the girl is the most baffling and mysterious that has come under my notice for many years, but we mean to keep on the job until the mystery is solved.

-Chief Rounds, as quoted by the Warren Daily Tribune, July 22, 1921 1:7

Rumors

As neighbor spoke to neighbor, passing the news of Mollie’s death and discussing the horror of the murder, they spun lurid tales involving the nature of the girl’s death. Someone began a rumor that Mollie’s head had been severed from her body. Another person suggested that in Mollie’s despair over her home life, she had committed suicide, possibly by drinking poison. Others, including some of authority, believed that Molly did not meet a violent end but rather died of shock or natural causes.

Police received the information that Mollie had been so out of control and impossible to parent, that Mr. and Mrs. Verbias were sending her to reform school. Whether the girl was truly scheduled to go is not known, but a rumor formed that Mollie went into a deep state of depression. Police formed the theory that perhaps in her unwillingness to go, the girl had taken her own life and the parents had placed Mollie’s body in the pasture out of fear they would be implicated. Investigators took this information seriously and Coroner Henshaw submitted Mollie’s stomach for chemical analysis. However, when speaking with Mollie’s school teachers, police found Mollie to be a very well-adjusted pupil, despite her troubled home-life.

The town gossips pointed many fingers at Mrs. Verbias, convinced that the mother knew more than she was telling police. Many had heard Mollie’s cries of pain coming from inside the home on several occasions throughout the prior months and witnessed Mrs. Verbias’ strange, dry-eyed demeanor following her daughter’s death.

The town grocer, Thomas Mullican, told investigators that he had observed Mollie walking along the railroad tracks around 4 o’clock with an unidentified male on the day before her body was discovered. She was near Kane’s corners and walking towards the direction of her home. The vague description Mullican provided matched the description some of Mollie’s family gave concerning a strange man they had seen Mollie with on other occasions. Many residents shared the belief that Mollie’s death had been sexually motivated, but the assailant was frightened off before he could molest her body.

A Niles resident tipped off the police about the presence of a man driving a buggy past the field where Mollie’s body had been found around noontime on Wednesday. They conjectured that possibly he was somehow involved in the murder and had dumped her body off the road in the high grass. The man was brought in to the police station for questioning, but he had no knowledge of the girl and was released.

The day prior to Mollie’s funeral, police conducted a thorough search throughout the Verbias home, but did not uncover any incriminating evidence. They also found no vials or indication of fatal poison having been present in the house. Though the search turned up nothing, investigators were certain that Mollie was murdered, either by a member of her family or by an unknown assailant who saw her alone in the pasture and took the opportunity to attack her. Though they had yet to receive the results of the analysis on Mollie’s stomach, they could hardly further entertain the thought of suicide by poison when a container to carry it had not been present at the home or near Mollie’s body.

Investigators noted how laundry day took place at the Verbias home the day Mollie’s body had been discovered. Though it could mean nothing, it also meant Mrs. Verbias had a chance to clean any traces of blood from clothing. On the other hand, they speculated that the marks on Mollie’s neck may have not exuded a large enough quantity of blood to transfer to another surface. They were not deep by any means and the small amount of blood may have quickly congealed in the wounds.

The Funeral

Mollie’s body lay in state at the Verbias home before her funeral on Saturday, July 23rd. She was encased in a white casket, surrounded by a vast array of flowers.

Robes of virginal whiteness concealed the ugly black bruises inflicted by the assassin, and the calm sleep of death enhanced the childish innocence of the small white face.

– The Niles Daily News, July 22, 1921, Page 1

A Hungarian priest from Youngstown led the 3 o’clock services, chanting verse in the family’s native language. Mourners cried at the right of Molly’s body and her siblings took one last look at their beautiful sister, knowing she would not have the chance to grow up with them, forever fourteen.

Investigators were present at the simple funeral, watching the family’s every movement, particularly the actions of the parents. The police remained quiet fixtures in the background, searching for any suspicious word, act, or insincere weeping.

Chief Rounds stated to the Niles Daily News, “If we knew who the murderer was, we would not arrest him until after the funeral. We do not wish to make any arrests until we are sure of what we are doing, but it is possible that some arrests may be made after the services.” (Niles Daily News, July 23, 1921, Pg 1)

The community became incensed at Round’s words, claiming if he knew who the killer was, they should be arrested immediately. In a corrected statement, Rounds said, “We would have considered it inhuman to take any member of the family into custody on suspicion until after the services. If we had positive proof of the identity of the criminal, however, we should not hesitate a second before placing them under arrest.” (Niles Daily News, July 25, 1921, Pg 1)

Mollie was laid to rest in Niles Union Cemetery.

Family Implicated

Coroner Henshaw received the results from the analysis on Mollie’s stomach on the morning of July 26th. He had hoped an easy explanation of poison would be found within the contents, but the results were disappointing. The chemist had found only undigested cheese, blackberries, and a starchy substance he believed to be bread. He found no trace of poison, vegetable alkaloids, or phenol, leaving authorities to move onto their next plan of action. They could finally act on the clues they had collected throughout the week since Mollie’s murder.

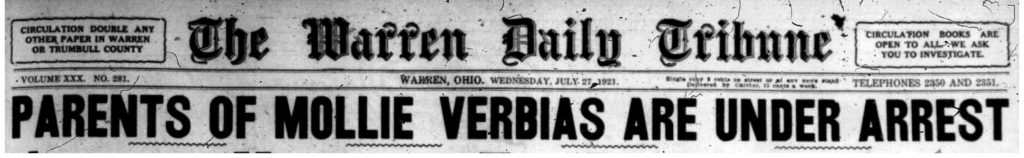

That same day at 4 o’clock, Officers Whittaker, Gilbert, and Mears took Mollie’s father, mother, and older brother Alex into custody. The three members of the family were locked in separate cells and were not allowed to communicate with one another. Mrs. Verbias raved constantly in her cell, shouting in her native language. She carried on all through the night, crying hysterically.

Since Mr. and Mrs. Verbias spoke very little English, all of the questioning was carried out through interpreters. Attorney Anthony A. Pessenieher of Youngstown represented the family. During examinations, the Verbias’ statements were inconsistent with one another as far as the time of day they last saw Mollie. However, each family member proved so overwrought with grief and confusion that Attorney Passenieher insisted police could not judge them on timing alone. The years of abuse by Mrs. Verbias were also brought up, not just the abuse of Mollie, but upon the other children as well. Investigators had spoken with the oldest daughter, Helen, and learned of her suicide attempt years earlier in attempt to escape the abuse at home. Yet the ill-treatment alone could not prove Mollie was murdered by Mrs. Verbias while carrying out punishment.

Investigators awaited the coroner’s verdict as to a cause of death, as it was difficult to move forward until such information was finalized. Police could not hold the family for very long as concrete evidence was lacking. However, with the arrival of a new crumb of information, the parents’ innocence and lack of involvement in Mollie’s death seemed to be clear. Chief Rounds received the statement by Niles resident Joe Kovak who claimed he saw Mollie at 6 or 6:30p.m. Wednesday as he was driving his cow to pasture. She was all alone and occupied picking berries. Because Kovach stated she had been wearing the blue sundress, the theory the dress had been placed on her after death was voided. Because this information of Mollie’s whereabouts was consistent with Mrs. Verbias’ account, Chief Rounds believed the woman was telling the truth.

Chief Rounds received a letter from police in Athens, Ohio who were investigating a similar crime in their district. They were without a suspect and proposed that the assailant could be a serial killer going from city to city, making him difficult to capture.

By July 30th, Mr. and Mrs. Verbias were released from jail, but Alex, remaining beneath the veil of suspicion, was detained longer.

Verdict

Coroner Henshaw scheduled the inquest for Wednesday, August 3rd. Many family members of the murdered girl and locals around the community were served notices, asking them to appear for questioning. They showed up and gave their testimonies, the interrogation lasting until the morning of the 4th, but the witnesses could provide no new information. Nothing was said to incriminate Mollie’s parents or brother and Henshaw set to work, drawing up a verdict. Unable to hold Alex any longer, he was released from jail.

On August 9th, Coroner Henshaw at last issued Mollie’s cause of death as manual strangulation. The faint finger markings proved the only evidence for her manner of death. Yet after the thorough inquest, investigators could not pin the murder on anyone and Mollie’s case went cold.

A Series Of Incidents

June 19th, 1916

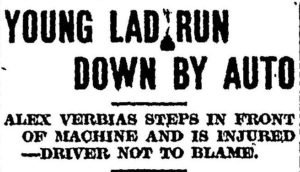

Years previous to the murder, 12-year-old Alex Verbias had a brush with death. On the afternoon of June 19th, 1916, he was walking along North Main Street in a rain shower with his cap pulled low over his eyes. When he attempted to cross the street, he stepped directly in front of a slow-moving roadster driven by W.T. Bell of Youngstown and was hit. He fell to the road, suffering a fractured rib, lacerated scalp, and a bruised knee. A passerby helped pick the boy up and drove Alex to the Niles Dry Goods Store to seek help, followed by Mr. Bell and his wife. Niles police officer Whittaker came along by chance and placed the boy in Mr. Bell’s vehicle. He led the roadster to Dr. Smith’s office where Alex was treated. Mr. Bell could not be blamed for the accident, but he felt quite badly and paid the lad’s medical bill.

Six years following his daughter’s murder, Mr. Verbias succumbed to pneumonia and lagrippe at his home. He was only 51 and left an obscure mark on the world. Though the Verbias family received considerable attention from the local community, we know very little about the patriarch and his personality. One recorded incident in June of 1916 occurred when Mr. Verbias’ cow wandered into a neighbor’s garden, destroying it. After the neighbor, Sam Natole, confronted Mr. Verbias, he refused to pay for the damages. Natole sued Mr. Verbias for the $5 value of the lost crops. Besides his brushes with the law, Joseph was hardly mentioned in the local papers and was not even afforded an obituary.

On May 17, 1929, Mollie’s 15-year-old sister Elizabeth “Lizzie” Verbias was injured in a car accident. She was riding in the backseat with her friend Minnie Shehedan in a vehicle driven by an older boy, Sam Maile. Sam lost control of the vehicle on Niles-Warren Road near Deforest. The car went off the road into the ditch and flipped over. All three suffered non-fatal injuries. Fortunately, a patrolman had been driving behind them and gave the girls a ride to Warren City Hospital. Sam refused the ride and never sought treatment. Lizzie was treated for lacerations about her face and Minnie for a broken nose and cuts around her eye.

An Unhappy Marriage

Alex Verbias was a troubled youth. The combined terrors of growing up in an abusive household and the murder of his little sister for which he was accused produced an erratic, depressed personality within him. Those closest to him noted how he became unhinged since Mollie’s death, recalling him as acting “queer”. Whenever he mentioned Mollie’s murder to family or friends, he repeated prophetically, “When I die I’m going to take a lot of people with me.”

He was eighteen when he wed Helen Krivac on May 26th, 1928 in a ceremony performed by Rev. S. Csepke at the Hungarian Presbyterian Church. The bride was dressed in an ornate white satin gown paired with satin slippers and held a bouquet bursting with roses and lilies of the valley. Her bridesmaids wore orange georgette dresses and held arrangements of roses and sweet peas. Following the nuptials, the German Hall hosted the bridal party as well as two hundred guests. Alex and Helen honeymooned in Michigan before returning to Niles to live with Alex’s mother at their home on Belmont Avenue.

Helen’s joy would last only as long as the beautiful ceremony. It could not have been easy for her to live with a woman as formidable as Mrs. Verbias who made ends meet by doing the washing, ironing, and cleaning for the better-off households of Niles. Alex would drink to excess and his moods were often unbearable.

Friday, October 18th, 1929

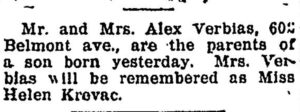

A bright spot among the darkness arrived with the birth of a son, Edward Joseph, on October 17, 1929. Alex was smitten with his child from the start, showering Edward with affection. Alex was excited about bringing his son up, planning his future before the boy could even walk. It was as if Alex suppressed all his dark energy, allowing his tiny son to hold all of life’s hope and promise.

Yet as Helen raised their beautiful baby boy in that gloomy Niles home, Alex failed to provide for his wife and the son he loved to extremes. Though employed as a cold roller for a Mahoning Valley steel plant for four years, he drank and gambled away his wages. Unable to raise her child in such conditions, Helen begged and pleaded with him to improve his character, but his intense devotion to his son was not enough to raise him from the demons’ clutches.

Finally, Helen said, “I can’t stand it any longer,” and left.

Just before Edward’s first birthday, she took the baby to the home of her parents, John and Anna Krivac, at 28 West Federal Street in Weathersfield. Three of Helen’s four brothers also lived at the house. Alex became incensed, often going to the Krivac home to argue with Helen, wishing to see his child. Helen and her parents ordered him to stay away, but he visited often and they allowed him entry every occasion so that he could see Edward. Mr. and Mrs. Krivac refused to get in the middle of Helen and Alex’s arguments, usually leaving the room while the pair quarreled.

Murderous Rampage

Alex’s coworkers and creditors held a very different opinion of the man who led a tumultuous home life. At work, he displayed a most respectable character. Foreman Jesse Lewis proclaimed Alex to be one of the hardest workers he had ever witnessed and that he was always punctual, never once hinting at having a problem with alcohol. The Niles Credit Bureau proclaimed Alex paid his loans on time, rating him “in the highest class”. With this information, we see Alex had two different sides and an ability to hide his melancholia and addictions behind the guise of normalcy.

Alex attempted reparations with his wife many times, beseeching Helen to come home. She rejected him, stating he would have to prove himself to her first by showing he could be a better husband and provider. However, his demons proved too raucous and he was unable to do as she asked.

In the late summer of 1930, Alex walked into the Krivac’s house, entering the kitchen and snatched Edward out of the crib kept on the floor. He ran off with his son and the Krivacs notified the police. Alex gave the boy up without issue but went into an intensely morose state. Ordered by the authorities to stay away from the Krivac’s house, he made threats that he would kill himself if Helen did not return home with their child.

On one occasion, Alex made several insults to one of Helen’s brothers and the pair came to fisticuffs. Alex often threatened that he would “get them all”.

On Monday, October 13th, one of Alex’s acquaintances stated the depressed father purchased a revolver on the pretense it would be used to ward off chicken thieves. That afternoon, Alex entered a speakeasy lounge and between sips of alcohol raved to the other patrons that he was going to kill himself and take everyone with him.

At 8:15 p.m. Alex came to the Krivac home, banging on the door and demanded to see his wife and child. At the time, only Helen, Edward, and Helen’s parents were home. Helen let him in and she conversed with him for several minutes in the foyer while her parents remained in the other room. Alex raised his voice, speaking angrily to her, and as soon as he began to threaten Helen, Mr. Krivac intervened. Mr. Krivac walked into the foyer after hearing Alex tell Helen he would kill her if she and Edward did not accompany him home.

Alex turned to his father-in-law and declared ominously, “I’ll shoot every damn one of you!”

He pulled a revolver from his coat and fired at Mr. Krivac who abruptly fell to the floor, the bullet having pierced his face.

Helen ran from the front hall, shrieking, “My God! Save my baby! Save my baby!”

Mrs. Krivac flew into the foyer, hands raised as if in surrender and said, “Alex you don’t know what you do! You don’t know what you do!”

Alex pointed the revolver at her and shot her through the eye. She staggered and fell dead just inside the front door.

Helen fled to the porch, shouting, “Help, help, someone come! Alex is killing us all!”

When a neighbor, Paul Kearney, ran out of his house he witnessed Alex chase Helen down and shoot her in the face. Bleeding profusely, Helen managed to run back in the house and scoop up her child. She ran howling from room to room, so out of her mind with terror, before she finally collapsed in her neighbor’s arms. Kearney placed the screaming baby into his kitchen crib and began making several phone calls, summoning help. When the ambulance arrived, medics could hardly believe what they saw, the bodies lying about with blood splattered on the walls and smeared across the floor. They tended to the blood-soaked baby who cried inconsolably inside his crib. They initially believed the child had been wounded and they brought him to the hospital with his mother and grandfather. When they loaded up Mr. Krivac for transportation, he was semiconscious. Mrs. Krivac was clearly gone and her body left where it fell as medics rushed the survivors to the hospital.

“He’ll kill my baby,” Helen moaned as medics loaded her into the ambulance, her face covered with blood.

Helen thought Alex had escaped, but while surveying the home the first responders discovered his body at the foot of the stairs. He bore a self-inflicted bullet wound behind his right ear while a dead hand clutched the revolver. The gun still contained two useable cartridges and another round of ammunition was found in his pocket. It was believed he planned to find his brothers-in-law at home and take their lives in a plot to massacre the Krivac family.

Spectators crowded around the home, their number in the hundreds, craning their necks to obtain a view of the bodies inside. They gaped at the murderer, his blood pooling out beneath him, a life wrought with grief and pain ended in violence. The Krivac’s son Louis returned home that evening to the collection of neighbors at his doorstep. He witnessed the blood everywhere, forming a zig-zag pattern across the kitchen floor. He found his mother laying bereft of all life and fell to her side. Moaning in grief, he ran to the second floor of the house in frantic search for his father. After learning that his father had survived and was at the hospital, he gathered his faculties enough to sign his mother’s death certificate as informant.

The bodies of Alex Verbias and Mrs. Anna Krivac were transported next door to the Kearney Funeral Home, victim lying next to murderer while they awaited funeral arrangements. Mrs. Krivac’s remains were returned to her home for the services and the body of Alex was brought to his mother at their Belmont Avenue home. Mrs. Krivac’s services were held at St. Stephen’s Church at 9 o’clock on the morning of Thursday, October 16th and was buried in St. Stephen Cemetery, having celebrated her 53rd birthday two days prior to her death. It appears Alex was unceremoniously buried in Niles Union Cemetery, his family baffled by his murderous rampage and suicide.

Helen and her father both recovered at Warren City Hospital, having each been shot through the jaw. Their survival was miraculous, as Alex had aimed to kill, but ultimately failed in his endeavor to take many souls with him. Unfortunately, Mr. Krivac died six years later from a respiratory ailment.

Crushed Beneath Vehicle

Sunday, August 2, 1936

Bazetta, Trumbull County, Ohio

As if all the untimely death and violence proved not enough for one family, the tragedies continued. Helen Laboda, daughter of Helen Verbias and Steve Laboda, was fourteen when she was killed, the same age her aunt Mollie was at the time of her murder. Helen and her sister Margaret had come to Bazetta Township to fish along Mosquito Creek with a group of friends. As they picnicked, they realized they needed more bread for their sandwiches, so Helen and Margaret hopped into the car of William Berenics, another Niles youth. He drove them to the Klondike store where they made the necessary purchase around 6 p.m. and headed back towards the creek. Yet on the way, William’s car skidded on a patch of gravel between the Lee Scoville and Raymond Hudson farms. He lost control and the vehicle careened over a ditch before flipping. Helen was thrown from the car and crushed beneath it, pressed face-down into the ditch. Her head was pinned so firmly beneath the vehicle that it took a group of passing motorists twenty minutes to extricate her. When she was finally pulled free, it was too late. Margaret and William were not injured, but suffered extreme shock as a result of the accident and Helen’s violent death.

Helen’s body was first taken to the Cortland Funeral Home and then transferred to the Laboda’s home on North Road. There, Rev. Steve Csepke officiated her funeral and she was buried in St. Stephen’s Cemetery. She left behind her bereaved parents, sister Margaret, and brother Steve Jr.

Death of the Matriarch

Mrs. Elizabeth Verbias died at the home of her daughter Helen and son-in-law Steve Laboda, just after Christmas in 1944, after suffering for three years with an asthmatic condition. She passed away under the care of the daughter she had so tormented and abused in her youth, driving her to attempted suicide. Mrs. Verbias’ calling hours were at the Rossi Funeral Home and the funeral services were held at the Hungarian Presbyterian Church. She was buried in Niles Union Cemetery. If she ever admitted to anyone in her family that she or Alex had strangled her daughter Mollie to death, the secret died with them. It seems easy to pin Mollie’s murder on Alex because he went on to kill so ruthlessly nearly a decade later. The police must have had their reasons for holding him under suspicion. Perhaps he did kill her, but it is also quite possible that their mother choked Mollie to death, an instance of abuse gone too far. Then again, maybe she had the misfortune of tarrying in the pasture at the wrong time, attacked by an unknown predator. To this day, the young girl’s murder is unsolved.

Killed Getting Off Bus

Wednesday, March 7th, 1945

Girard, Trumbull County, Ohio

Elizabeth, Alex and Mollie’s younger sister who had been injured as a teen in a car accident, grew up to marry Pasquale (Patrick) Rinaldo Dinard and settled in Girard. Patrick, who was known by his nickname “Push”, worked for the Ohio Leather Co. in Girard. He was also a member of the FOE Lodge of Girard and was well-known and liked throughout the Niles community. After a day’s work one day, he descended the stairs of a Penn-Ohio coach at the corner of North State Street and Smithsonian Avenue. As he crossed the street in front of the bus, he did not see the oncoming truck before he walked right into it. A Blackstone-Reese Ambulance rushed him to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, but he was dead on arrival. Besides the grief imposed on his wife by his loss, he left a wide group of extended family in the area. He was buried in Niles Union Cemetery. Elizabeth remarried to Michael Niebauer who died in 1971. She had no children from either marriage.

Life Goes On

Friday, March 27th, 1953

Helen Krivac Verbias married Samuel Morrall on February 6, 1936 in Cuyahoga County, and settled in Weathersfield. The couple had a daughter, Joanne Marie, in 1937. Edward took on his step-father’s surname Morrall and attended McKinley school. He played trombone in the school band and graduated in 1948. Edward would grow up to become the music director for Central Baptist Church. Both Edward and his half-sister Joanne wed their spouses in 1955 with Edward marrying Rae Gwendolyn Monteith and Joanne marrying Charles Fanos George in a lavish ceremony. Helen enjoyed several grandchildren from these pairings. She was a member of the Cardettes Club and often hosted grand lunches for the group. The family lived wonderfully, were largely integrated into Niles society, and were well respected. For Helen to have endured such tragedy as a young woman, the bulk of her life was spent in happiness. She outlived her son Edward by five years, passing away in 2005 at the age of 94.

August 10th, 1954

Helen and Edward were able to start over in a way, though the horror of that October night in 1930 remained with them until they died. No branch of the Verbias family seemed to exist untouched from violence and untimely death. One can only imagine the heartache the connected Verbias, Krivac, Laboda, and Dinard families endured from these senseless tragedies. My hope is that the dark shadow that cloaked their lives has dissipated and their souls are at peace.

Note: Conflicting reports give differing accounts of who actually discovered Mollie’s body. The Warren Tribune said it was a man coming home from work who segued into the pasture to pick berries in Mason’s Woods. The Niles Daily News claimed it was two little boys who entered the grassy area along the way to pick berries.

Resources

- Immigration: New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924, familysearch.org

- Young Lad Run Down By Auto: The Niles Daily News, Monday, June 19th, 1916, Pg 5

- Gasper Logar WWI Draft Registration: World War I Selective Service System draft registration cards, 1917-1918, familysearch.org

- Slays Child: The Niles Daily News 7-22-1921, Pgs 1 and 5

- Posses Hunt Assailant of Niles School Girl; Finger Prints on Neck: The Sandusky Star-Journal (Sandusky, Ohio) · 22 Jul 1921, Fri · Page 1

- Body of 14-Year-Old Mollie Verbias Is Found In Thicket: Warren Daily Tribune, 22 Jul 1921 Pgs 1:7 and 5:4

- Mystery Is Unsolved As Police Work: Warren Daily Tribune, July 23, 1921 1:1

- Girl’s Body Found In Woods: The Bucyrus Evening Telegraph, 23 Jul 1921, Sat Pg 6

- Bury Girl As Police Trace Clues: Niles Daily Times, July 23, 1921, Pg 1

- Death Mystery Still Unsolved: Niles Daily News, July 25, 1921, Pg 1

- No Poison Was Found: Warren Daily Tribune, July 26, 1921 1:6

- Parents of Mollie Verbias Are Under Arrest – Taken Into Custody By Police of Niles: Warren Daily Tribune: July 27, 1921 1:7

- Coroner is Not Talking Verbias Case: Warren Daily Tribune, July 28, 1921 1:4

- Probing Verbias Murder: The Niles Daily Times, July 28, 1921, Pg 1

- Hold Brother Of Dead Girl: Warren Daily Tribune, July 30, 1921 1:2

- Verbias Case Inquest Aug. 3: The Niles Daily News, July 22, 1921

- No Decision In Verbias Inquest: The Niles Daily News, August 4, 1921

- Niles Girl Was Choked Is Verdict: Warren Daily Tribune, August 9th, 1921 1:1

- Krivac-Verbias Marriage: Niles Daily Times Monday May 28, 1928, Pg 4

- Girls Injured in Accident: Niles Daily Times, Saturday, May 18, 1929

- Alex Verbias Death Certificate: “Ohio Deaths, 1908-1953,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-67N9-74D?cc=1307272&wc=MD9F-KTG%3A287601401%2C294672102 : 21 May 2014), 1930 > 60501-63300 > image 2813 of 3129.

- Death Threat Fulfilled: News-Journal, 14 Oct 1930, Tue, Page 1

- Crazed Husband Injures Wife and Her Father: Niles Daily Times, Tuesday, October 14th, 1930, Pgs 1 and 5

- Crazed Man Shoots 3, Takes Own Life: Warren Tribune Chronicle October 14, 1930 Pg 1

- Niles Man Wounds Wife, Her Father: Warren Tribune Chronicle 14 Oct 1930 1:8

- Last Rites For Killer, Victim: Niles Daily Times, 10-15-1930, Pg 1

- Situations Wanted: Niles Daily Times, Thursday, August 24th, 1933, Pg 14

- Elizabeth Verbias Obituary: Warren Tribune Chronicle 23 Dec 1944, Pg 7

- Funeral Services: Niles Daily Times, Thursday, December 28th, 1944, Pg 3

- Car Skids In Gravel, Hits Ditch: Warren Tribune Chronicle, August 3, 1936 1:1

- Helen Laboda, North Road, Is Victim: Niles Daily Times, Monday August 3, 1936, Pg 1

- Girard Man Leaves Bus, Killed By Passing Truck: Niles Daily Times, Thursday, March 8th, 1945, Pg 1

- Samuel Morrall and Helen Krivac Marriage Record: Marriage records (Cuyahoga County, Ohio), 1810-1941; indexes, 1810-1952, familysearch.org